![STR1]()

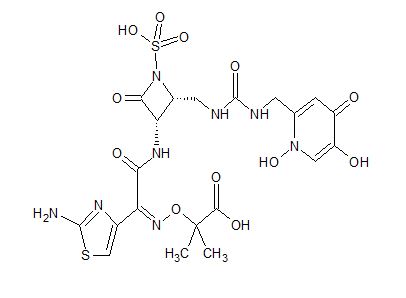

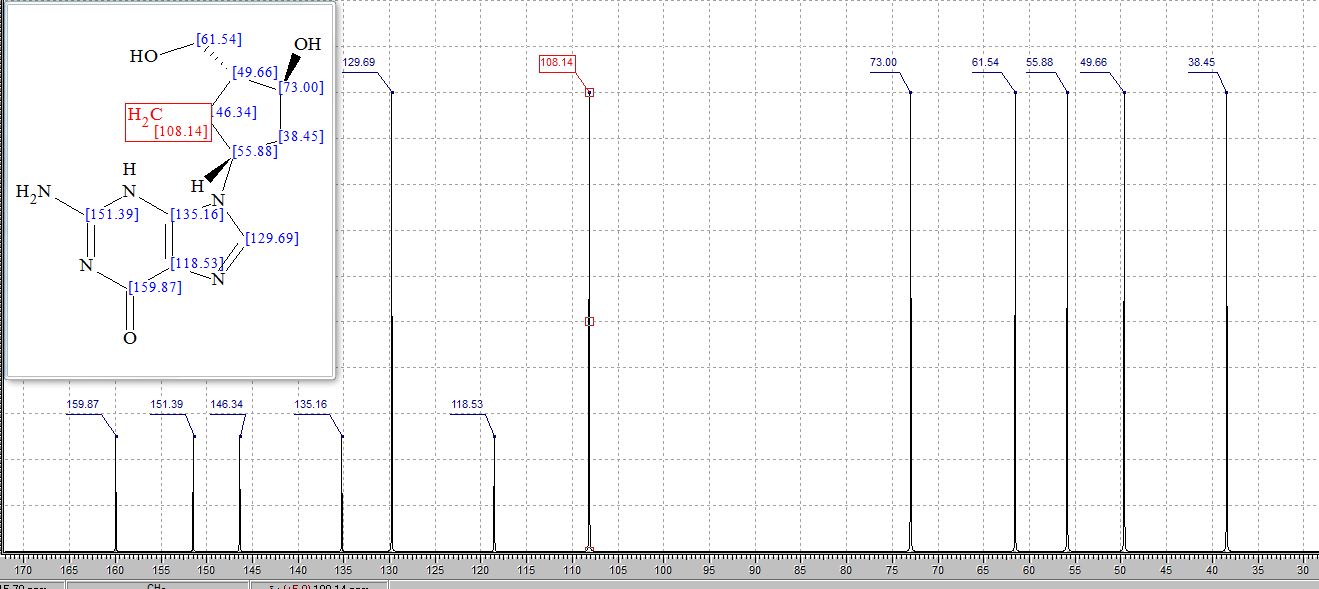

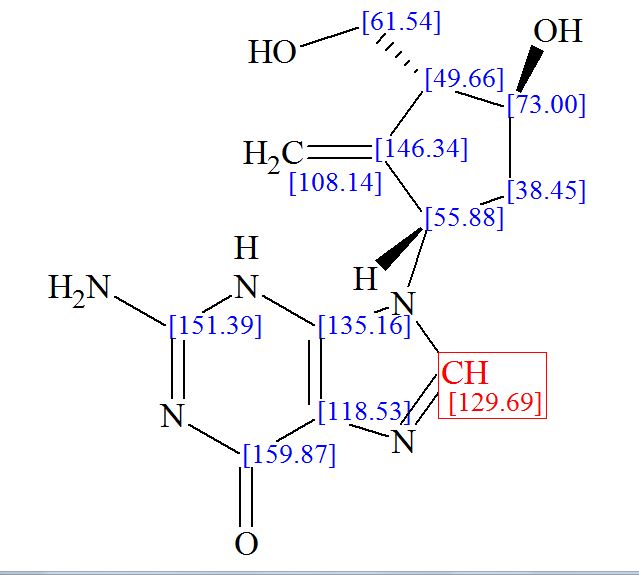

Pfizer’s monobactam PF-?

1380110-34-8, C20 H24 N8 O12 S2, 632.58

Propanoic acid, 2-[[(Z)-[1-(2-amino-4-thiazolyl)-2-[[(2R,3S)-2-[[[[[(1,4-dihydro-1,5-dihydroxy-4-oxo-2-pyridinyl)methyl]amino]carbonyl]amino]methyl]-4-oxo-1-sulfo-3-azetidinyl]amino]-2-oxoethylidene]amino]oxy]-2-methyl-

2-((Z)-1-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl)-2-((2R,3S)-2-((((1,5-dihydroxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyridin-2-yl)methoxy)carbonylamino)methyl)-4-oxo-1-sulfoazetidin-3-ylamino)-2-oxoethylideneaminooxy)-2-methylpropanoic Acid

2-[[(Z)-[1-(2-Amino-4-thiazolyl)-2-[[(2R,3S)-2-[[[[[(1,4-dihydro-1,5-dihydroxy-4-oxo-2-pyridinyl)methyl]amino]carbonyl]amino]methyl]-4-oxo-1-sulfo-3-azetidinyl]amino]-2-oxoethylidene]amino]oxy]-2-methylpropanoic acid

Monobactams are a class of antibacterial agents which contain a monocyclic beta-lactam ring as opposed to a beta-lactam fused to an additional ring which is found in other beta-lactam classes, such as cephalosporins, carbapenems and penicillins. The drug Aztreonam is an example of a marketed monobactam; Carumonam is another example. The early studies in this area were conducted by workers at the Squibb Institute for Medical Research, Cimarusti, C. M. & R.B. Sykes: Monocyclic β-lactam antibiotics. Med. Res. Rev. 1984, 4, 1 -24. Despite the fact that selected

monobacatams were discovered over 25 years ago, there remains a continuing need for new antibiotics to counter the growing number of resistant organisms.

Although not limiting to the present invention, it is believed that monobactams of the present invention exploit the iron uptake mechanism in bacteria through the use of siderophore-monobactam conjugates. For background information, see: M. J. Miller, et al. BioMetals (2009), 22(1 ), 61-75.

The mechanism of action of beta-lactam antibiotics, including monobactams, is generally known to those skilled in the art and involves inhibition of one or more penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), although the present invention is not bound or limited by any theory. PBPs are involved in the synthesis of peptidoglycan, which is a major component of bacterial cell walls.

WO 2012073138

https://www.google.com/patents/WO2012073138A1?cl=en

Example 4, Route 1

2-({[(1Z)-1 -(2-amino-1 ,3-thiazol-4-yl)-2-({(2f?,3S)-2-[({[(1 ,5-dihydroxy-4-oxo-1 ,4- dihydropyridin-2-yl)methyl]carbamoyl}amino)methyl]-4-oxo-1 -sulfoazetidin-3- yl}amino)-2-oxoethylidene]amino}oxy)-2-methylpropanoic acid, bis sodium salt

(C92-Bis Na Salt).

C92-bis Na salt

Step 1 : Preparation of C90. A solution of C26 (16.2 g, 43.0 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (900 mL) was treated with 1 , 1 ‘-carbonyldiimidazole (8.0 g, 47.7 mmol). After 5 minutes, the reaction mixture was treated with a solution of C9 (15 g, 25.0 mmol) in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (600 mL) at room temperature. After 15 hours, the solvent was removed and the residue was treated with ethyl acetate (500 mL) and water (500 mL). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was back extracted with additional ethyl acetate (300 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed with brine solution (500 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified via chromatography on silica gel (ethyl acetate / 2-propanol) to yield C90 as a yellow foam. Yield: 17.44 g, 19.62 mmol, 78%. LCMS m/z 889.5 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 1 1 .90 (br s, 1 H), 9.25 (d, J=8.7 Hz, 1 H), 8.40 (br s, 1 H), 7.98 (s, 1 H), 7.50-7.54 (m, 2H), 7.32-7.47 (m, 8H), 7.28 (s, 1 H), 6.65 (br s, 1 H), 6.28 (br s, 1 H), 5.97 (s, 1 H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 5.18 (dd, J=8.8, 5 Hz, 1 H), 4.99 (s, 2H), 4.16-4.28 (m, 2H), 3.74-3.80 (m, 1 H), 3.29-3.41 (m, 1 H), 3.13-3.23 (m, 1 H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.39 (br s, 12H).

Step 2: Preparation of C91. A solution of C90 (8.5 g, 9.6 mmol) in anhydrous N,N- dimethylformamide (100 mL) was treated sulfur trioxide /V,/V-dimethylformamide complex (15.0 g, 98.0 mmol). The reaction was allowed to stir at room temperature for 20 minutes then quenched with water (300 mL). The resulting solid was collected by filtration and dried to yield C91 as a white solid. Yield: 8.1 g, 8.3 mmol, 87%. LCMS m/z 967.6 (M-1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1 1.62 (br s, 1 H), 9.29 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1 H), 9.02 (s, 1 H), 7.58-7.61 (m, 2H), 7.38-7.53 (m, 9H), 7.27 (s, 1 H), 7.07 (s, 1 H), 6.40 (br d, J=8 Hz, 1 H), 5.55 (s, 2H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 5.20 (dd, J=8.8, 5.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.46 (br dd, half of ABX pattern, J=17, 5 Hz, 1 H), 4.38 (br dd, half of ABX pattern, J=17, 6 Hz, 1 H), 3.92-3.98 (m, 1 H), 3.79-3.87 (m, 1 H), 3.07-3.17 (m, 1 H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1 .39 (s, 3H), 1 .38 (s, 12H).

Step 3: Preparation of C92. A solution of C91 (8.1 g, 8.3 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (200 mL) was treated with 1 M boron trichloride in p-xylenes (58.4 mL, 58.4 mmol) and allowed to stir at room temperature for 15 minutes. The reaction mixture was cooled in an ice bath, quenched with 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (61 mL), and the solvent was removed in vacuo. A portion of the crude product (1 g) was purified via reverse phase chromatography (C-18 column; acetonitrile / water gradient with 0.1 % formic acid modifier) to yield C92 as a white solid. Yield: 486 mg, 0.77 mmol. LCMS m/z 633.3 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.22 (d, J=8.7 Hz, 1 H), 8.15 (s, 1 H), 7.26-7.42 (br s, 2H), 7.18-7.25 (m, 1 H), 6.99 (s, 1 H), 6.74 (s, 1 H), 6.32-6.37 (m, 1 H), 5.18 (dd, J=8.7, 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 4.33 (br d, J=4.6 Hz, 2H), 3.94-4.00 (m, 1 H), 3.60-3.68 (m, 1 H), 3.19-3.27 (m, 1 H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H).

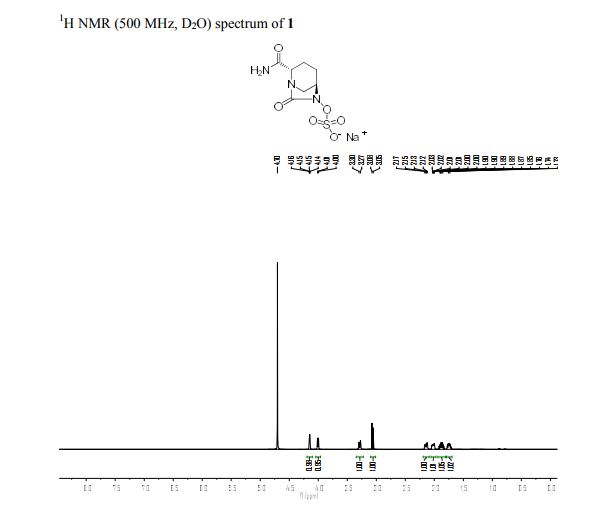

Step 4: Preparation of C92-Bis Na Salt. A flask was charged with C92 (388 mg, 0.61 mmol) and water (5.0 mL). The mixture was cooled in an ice bath and treated dropwise with a solution of sodium bicarbonate (103 mg, 1.52 mmol) in water (5.0 mL). The sample was lyophilized to yield C92-Bis Na Salt as a white solid. Yield: 415 mg, 0.61 mmol, quantitative. LCMS m/z 633.5 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D20) δ 7.80 (s, 1 H), 6.93 (s, 1 H), 6.76 (s, 1 H), 5.33 (d, J=5.7 Hz, 1 H), 4.44 (ddd, J=6.0, 6.0, 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 4.34 (AB quartet, JAB=17.7 Hz, ΔνΑΒ=10.9 Hz, 2H), 3.69 (dd, half of ABX pattern, J=14.7, 5.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.58 (dd, half of ABX pattern, J=14.7, 6.2 Hz, 1 H), 1.44 (s, 3H), 1.43 (s, 3H).

Alternate preparation of C92

Step 1 : Preparation of C93. An Atlantis pressure reactor was charged with 10% palladium hydroxide on carbon (0.375 g, John Matthey catalyst type A402028-10), C91 (0.75 g, 0.77 mmol) and treated with ethanol (35 mL). The reactor was flushed with nitrogen and pressurized with hydrogen (20 psi) for 20 hours at 20 °C. The reaction mixture was filtered under vacuum and the filtrate was concentrated using the rotary evaporator to yield C93 as a tan solid. Yield: 0.49 g, 0.62 mmol, 80%. LCMS m/z 787.6 (M-1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1 1.57 (br s, 1 H), 9.27 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.16 (s, 1 H), 7.36 (br s, 1 H), 7.26 (s, 1 H), 7.00 (s, 1 H), 6.40 (br s, 1 H), 5.18 (m, 1 H), 4.35 (m, 2H), 3.83 (m, 1 H), 3.41 (m, 1 H), 3.10 (m, 1 H), 1.41 (s, 6H), 1.36 (s, 18H).

Step 2: Preparation of C92. A solution of C93 (6.0 g, 7.6 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (45 mL) at 0 °C was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (35.0 mL, 456 mmol). The mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 2 hours. The reaction mixture was cannulated into a solution of methyl ferf-butyl ether (100 mL) and heptane (200 mL). The solid was collected by filtration and washed with a mixture of methyl ferf-butyl ether (100 mL) and heptane (200 mL) then dried under vacuum. The crude product (~5 g) was purified via reverse phase chromatography (C-18 column; acetonitrile / water gradient with 0.1 % formic acid modifier) and lyophilized to yield C92 as a pink solid. Yield: 1.45 g, 2.29 mmol. LCMS m/z 631.0 (M-1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-de) δ 9.20 (d, J=8.7 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.24-7.40 (br s, 2H), 7.16-7.23 (m, 1H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.31-6.35 (m, 1H), 5.15 (dd, J=8.7, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (br d, J=4.6 Hz, 2H), 3.92-3.98 (m, 1H), 3.58-3.67 (m, 1H), 3.17-3.25 (m, 1H), 1.37 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 3H).

Example 4, route 2

2-({[(1Z)-1-(2-amino-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)-2-({(2 ?,3S)-2-[({[(1,5-dihydroxy-4-oxo-^ dihydropyridin-2-yl)methyl]carbamoyl}amino)methyl]-4-oxo-1-sulfoazetidin-3- yl}amino)-2-oxoethylidene]amino}oxy)-2-methylpropanoic acid (C92).

lt

single

enantiomer

Step 1. Preparation of C95. A solution of C94 (50.0 g, 189.9 mmol) in

dichloromethane (100 mL) was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (50.0 mL, 661.3 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 hours. The dichloromethane and trifluoroacetic acid was displaced with toluene (4 x 150 mL) using vacuum, to a final volume of 120 mL. The solution was added to heptane (250 mL) and the solid was collected by filtration. The solid was washed with a mixture of toluene and heptane (1 : 3, 60 mL), followed by heptane (2 x 80 mL) and dried under vacuum at 50 °C for 19 hours to afford C95 as a solid. Yield: 30.0 g, 158 mmol, 84%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) δ 9.66 (s, 1 H), 7.86 – 7.93 (m, 2H), 7.73 – 7.80 (m, 2H), 4.57 (s, 2H). HPLC retention time 5.1 minutes; column: Agilent Extended C-18 column (75 mm x 3 mm, 3.5 μηη); column temperature 45 °C; flow rate 1.0 mL / minute; detection UV 230 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = acetonitrile (100%), solvent B = acetonitrile (5%) in 10 mM ammonium acetate; gradient elusion: 0-1.5 minutes solvent B (100%), 1.5-10.0 minutes solvent B (5%), 10.0-13.0 minutes solvent B (100%); total run time 13.0 minutes.

Step 2: Preparation of C96-racemic. A solution of C95 (32.75 g; 173.1 mmol) in dichloromethane (550 mL) under nitrogen was cooled to 2 °C. The solution was treated with 2,4-dimethoxybenzylamine (28.94 g, 173.1 mmol) added dropwise over 25 minutes, maintaining the temperature below 10 °C. The solution was stirred for 10 minutes at 2 °C and then treated with molecular sieves (58.36 g, UOP Type 3A). The cold bath was removed and the reaction slurry was stirred for 3 hours at room temperature. The slurry was filtered through a pad of Celite (34.5 g) and the filter cake was rinsed with dichloromethane (135 mL). The dichloromethane filtrate (imine solution) was used directly in the following procedure.

A solution of A/-(ferf-butoxycarbonyl)glycine (60.6 g, 346.1 mmol) in

tetrahydrofuran (622 mL) under nitrogen was cooled to -45 °C and treated with triethylamine (38.5 g, 380.8 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 15 minutes at -45 °C and then treated with ethyl chloroformate (48.8 g, 450 mmol) over 15 minutes. The reaction mixture was stirred at -50 °C for 7 hours. The previously prepared imine solution was added via an addition funnel over 25 minutes while maintaining the reaction mixture temperature below -40 °C. The slurry was treated with triethylamine (17.5 g, 173 mmol) and the reaction mixture was slowly warmed to room temperature over 5 hours and stirred for an additional 12 hours. The reaction slurry was charged with water (150 mL) and the volatiles removed using a rotary evaporator. The reaction mixture was charged with additional water (393 mL) and the volatiles removed using a rotary evaporator. The mixture was treated with methyl ferf-butyl ether (393 mL) and vigorously stirred for 1 hour. The solid was collected by vacuum filtration and the filter cake was rinsed with a mixture of methyl ferf-butyl ether and water (1 : 1 , 400 mL). The solid was collected and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C for 16 hours to afford C96- racemic. Yield: 55.8 g, 1 13 mmol, 65%. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.85 (s, NH), 7.80 (s, 4H), 6.78 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.25 (m, 1 H), 6.10 (m, 1 H), 4.83 (m, 1 H), 4.38 (d, J=9.5 Hz, 1 H), 3.77-3.95 (m, 3H), 3.62 (s, 3H), 3.45 (m, 1 H), 3.40 (s, 3H), 1.38 (s, 9H). HPLC retention time 6.05 minutes; XBridge C8 column (4.6 x 75 mm, 3.5 μηη); column temperature 45 °C; flow rate 2.0 mL/minute; detection UV 210 nm, 230 nm, and 254 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = methanesulfonic acid (5%) in 10 mmol sodium octylsulfonate, solvent B = acetonitrile (100%); gradient elusion: 0-1.5 minutes solvent A (95%) and solvent B (5%), 1.5-8.5 minutes solvent A (5%) and solvent B (95%), 8.5- 10.0 minutes solvent A (5%) and solvent B (95%), 10.01 -12.0 minutes solvent A (95%) and solvent B (5%); total run time 12.0 minutes.

Step 3: Preparation of C97-racemic. A solution of C96-racemic (15.0 g, 30.3 mmol) in ethyl acetate (150 mL) under nitrogen was treated with ethanolamine (27.3 mL, 454.1 mmol). The reaction mixture was heated at 90 °C for 3 hours and then cooled to room temperature. The mixture was charged with water (150 mL) and the layers separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (75 mL) and the combined organic layers washed with water (2 x 150 mL) followed by saturated aqueous sodium chloride (75 mL). The organic layer was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered and the filtrate concentrated to a volume of 38 mL. The filtrate was treated with heptane (152 mL) and the solid was collected by filtration. The solid was washed with heptane and dried at 50 °C in a vacuum oven overnight to yield C97-racemic as a solid. Yield: 9.68 g, 26.5 mmol, 88%. LCMS m/z 967.6 (M-1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.64 (d, J=9.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.14 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.56 (s, 1 H), 6.49 (dd, J=8.20, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.78 (dd, J=9.37, 5.1 Hz, 1 H), 4.30 (d, J=14.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.14 (d, J=14.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.45 – 3.53 (m, 1 H), 2.65 – 2.75 (m, 1 H), 2.56 – 2.64 (m, 1 H), 1.38 (s, 9H), 1.30 – 1.35 (m, 2H). HPLC retention time 5.1 minutes; column: Agilent Extended C-18 column (75 mm x 3 mm, 3.5 μΐη); column temperature 45 °C; flow rate 1.0 mL / minute;

detection UV 230 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = acetonitrile (100%), solvent B = acetonitrile (5%) in 10 mM ammonium acetate; gradient elusion: 0-1 .5 minutes solvent B (100%), 1 .5-10.0 minutes solvent B (5%), 10.0-13.0 minutes solvent B (100%); total run time 13.0 minutes. Step 4: Preparation of C97-(2R,3S) enantiomer. A solution of C97-racemic (20.0 g, 54.7 mmol) in ethyl acetate (450 mL) was treated with diatomaceous earth (5.0 g) and filtered through a funnel charged with diatomaceous earth. The filter cake was washed with ethyl acetate (150 mL). The filtrate was charged with diatomaceous earth (20.0 g) and treated with (-)-L-dibenzoyltartaric acid (19.6 g, 54.7 mmol). The slurry was heated at 60 °C for 1.5 hours and then cooled to room temperature. The slurry was filtered and the solid washed with ethyl acetate (90 mL). The solid was collected and dried at 50 °C in a vacuum oven for 17 hours to yield C97-(2R,3S) enantiomer as a solid (mixed with diatomaceous earth). Yield: 17.3 g, 23.9 mmol, 43.6%, 97.6% ee. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-de) δ 7.89 – 7.91 (m, 4H), 7.59 – 7.65 (m, 3H), 7.44 – 7.49 (m, 4H), 7.09 (d, J=8.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.53 (d, J=2.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.49 (dd, J=8.3, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 5.65 (s, 2H), 4.85 (dd, J=9.3, 4.9 Hz, 1 H), 4.30 (d, J=15.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.10 (d, J=15.3 Hz, 1 H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.68 – 3.70 (m, 1 H), 2.92 – 2.96 (dd, J=13.6, 5.4 Hz, 1 H), 2.85 – 2.90 (dd, J=13.6, 6.3 Hz, 1 H), 1.36 (s, 9H). HPLC retention time 5.1 minutes; column: Agilent Extended C-18 column (75 mm x 3 mm, 3.5 μηη); column temperature 45 °C; flow rate 1.0 mL / minute; detection UV 230 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = acetonitrile (100%), solvent B = acetonitrile (5%) in 10 mM ammonium acetate; gradient elusion: 0-1 .5 minutes solvent B (100%), 1.5-10.0 minutes solvent B (5%), 10.0-13.0 minutes solvent B (100%); total run time 13.0 minutes. Chiral HPLC retention time 9.1 minutes; column: Chiralcel OD-H column (250 mm x 4.6 mm); column temperature 40 °C; flow rate 1 .0 mL / minute; detection UV 208 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = ethanol (18%), solvent B = heptane (85%); isocratic elusion; total run time 20.0 minutes.

Step 5: Preparation of C98-(2R,3S) enantiomer. A solution of C97-(2R,3S) enantiomer. (16.7 g, 23.1 mmol) in ethyl acetate (301 mL) was treated with diatomaceous earth (18.3 g) and 5% aqueous potassium phosphate tribasic (182 mL). The slurry was stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature, then filtered under vacuum and the filter cake washed with ethyl acetate (2 x 67 mL). The filtrate was washed with 5% aqueous potassium phosphate tribasic (18 mL) and the organic layer dried over magnesium sulfate. The solid was filtered and the filter cake washed with ethyl acetate (33 mL). The filtrate was concentrated to a volume of 42 mL and slowly added to heptane (251 mL) and the resulting solid was collected by filtration. The solid was washed with heptane and dried at 50 °C in a vacuum oven for 19 hours to yield C98- (2R,3S) enantiomer as a solid. Yield: 6.4 g, 17.5 mmol, 76%, 98.8% ee. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-de) δ 7.64 (d, J=9.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.14 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.56 (s, 1 H), 6.49 (dd, J=8.20, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.78 (dd, J=9.37, 5.1 Hz, 1 H), 4.30 (d, J=14.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.14 (d, J=14.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.45 – 3.53 (m, 1 H), 2.65 – 2.75 (m, 1 H), 2.56 – 2.64 (m, 1 H), 1.38 (s, 9H), 1.30 – 1.35 (m, 2H). HPLC retention time 5.2 minutes; column: Agilent Extended C-18 column (75 mm x 3 mm, 3.5 μηη); column temperature 45 °C; flow rate 1.0 mL / minute; detection UV 230 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = acetonitrile (100%), solvent B = acetonitrile (5%) in 10 mM ammonium acetate; gradient elusion: 0-1 .5 minutes solvent B (100%), 1.5-10.0 minutes solvent B (5%), 10.0-13.0 minutes solvent B (100%); total run time 13.0 minutes. Chiral HPLC retention time 8.7 minutes; column: Chiralcel OD-H column (250 mm x 4.6 mm); column temperature 40 °C; flow rate 1.0 mL / minute; detection UV 208 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = ethanol (18%), solvent B = heptane (85%); isocratic elusion; total run time 20.0 minutes.

Step 6: Preparation of C99. A solution of potassium phosphate tribasic N-hydrate (8.71 g, 41 .05 mmol) in water (32.0 mL) at 22 °C was treated with a slurry of C26- mesylate salt (12.1 g, 27.4 mmol, q-NMR potency 98%) in dichloromethane (100.00 mL). The slurry was stirred for 1 hour at 22 °C. The reaction mixture was transferred to a separatory funnel and the layers separated. The aqueous layer was back extracted with dichloromethane (50.0 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered under vacuum and the filter cake washed with

dichloromethane (2 x 16 mL). The filtrate (-190 mL, amine solution) was used directly in the next step.

A solution of 1 ,1 ‘-carbonyldiimidazole (6.66 g, 41 .0 mmol) in dichloromethane (100 mL) at 22 °C under nitrogen was treated with the previously prepared amine solution (-190 mL) added dropwise using an addition funnel over 3 hour at 22 °C with stirring. After the addition, the mixture was stirred for 1 hour at 22 °C, then treated with C98-(2R,3S) enantiomer. (10.0 g, 27.4 mmol) followed by /V,/V-dimethylformamide (23.00 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at 22 °C for 3 hours and then heated at 40 °C for 12 hours. The solution was cooled to room temperature and the dichloromethane was removed using the rotary evaporator. The reaction mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate (216.0 mL) and washed with 10% aqueous citric acid (216.0 mL), 5% aqueous sodium chloride (2 x 216.0 mL), dried over magnesium sulfate and filtered under vacuum. The filter cake was washed with ethyl acetate (3 x 13 mL) and the ethyl acetate solution was concentrated on the rotary evaporator to a volume of (-1 10.00 mL) providing a suspension. The suspension (~1 10.00 mL) was warmed to 40 °C and transferred into a stirred solution of heptane (22 °C) over 1 hour, to give a slurry. The slurry was stirred for 1 hour and filtered under vacuum. The filter cake was washed with heptane (3 x 30 mL) and dried under vacuum at 50 °C for 12 hours to afford C99 as a solid. Yield: 18.1 g, 24.9 mmol, 92%. LCMS m/z 728.4 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.09 (s, 1 H), 7.62 (d, J=9.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.33-7.52 (m, 10H), 7.07 (d, J=8.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.51 (d, J=2.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.50 (m, 1 H), 6.44 (dd, J=8.3, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.12 (m, 1 H), 6.07 (s, 1 H), 5.27 (s, 2H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 4.73 (dd, J=9.4, 5.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.38 (d, J=15.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.19 (m, 2H), 3.99 (d, J=15.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.48 (m, 1 H), 3.28 (m, 1 H), 3.12 (m, 1 H), 1 .37 (s, 9H).

Step 7: Preparation of C100. A solution of C99 (46.5 g, 63.9 mmol) in acetonitrile (697 mL and water (372 mL) was treated with potassium persulfate (69.1 g, 255.6 mmol) and potassium phosphate dibasic (50.1 g, 287.5 mmol). The biphasic mixture was heated to 75 °C and vigorously stirred for 1.5 hours. The pH was maintained between 6.0-6.5 by potassium phosphate dibasic addition (-12 g). The mixture was cooled to 20 °C, the suspension was filtered and washed with acetonitrile (50 mL). The filtrate was concentrated using the rotary evaporator and treated with water (50 mL) followed by ethyl acetate (200 mL). The slurry was stirred for 2 hours at room temperature, filtered and the solid dried under vacuum at 40 °C overnight. The solid was slurried in a mixture of ethyl acetate and water (6 : 1 , 390.7 mL) at 20 °C for 1 hour then collected by filtration. The solid was dried in a vacuum oven to yield C100. Yield: 22.1 g, 38.3 mmol, 60%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.17 (br s, 1 H), 7.96 (s, 1 H), 7.58 (d, J=9.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.29-7.50 (m, 10H), 6.49 (dd, J=8.0, 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 6.08 (dd, J=5.6, 5.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.93 (s, 1 H), 5.22 (s, 2H), 4.96 (s, 2H), 4.77 (dd, J=9.6, 5.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.16 (m, 2H), 3.61 (m, 1 H), 3.1 1 (m, 2H), 1.36 (s, 9H). HPLC retention time 6.17 minutes; XBridge C8 column (4.6 x 75 mm, 3.5 μηη); column temperature 45 °C; flow rate 2.0 mL/minute; detection UV 210 nm, 230 nm, and 254 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = methanesulfonic acid (5%) in 10 mmol sodium octylsulfonate, solvent B = acetonitrile (100%); gradient elusion: 0-1 .5 minutes solvent A (95%) and solvent B (5%), 1.5-8.5 minutes solvent A (5%) and solvent B (95%), 8.5-10.0 minutes solvent A (5%) and solvent B (95%), 10.01- 12.0 minutes solvent A (95%) and solvent B (5%); total run time 12.0 minutes.

Step 8: Preparation of C101. A solution of trifluoroacetic acid (120 mL, 1550 mmol) under nitrogen was treated with methoxybenzene (30 mL, 269 mmol) and cooled to -5 °C. Solid C100 (17.9 g, 31.0 mmol) was charged in one portion at -5 °C and the resulting mixture stirred for 3 hours. The reaction mixture was cannulated with nitrogen pressure over 15 minutes to a stirred mixture of Celite (40.98 g) and methyl ferf-butyl ether (550 mL) at 10 °C. The slurry was stirred at 16 °C for 30 minutes, then filtered under vacuum. The filter cake was rinsed with methyl ferf-butyl ether (2 x 100 mL). The solid was collected and slurried in methyl ferf-butyl ether (550 mL) with vigorous stirring for 25 minutes. The slurry was filtered by vacuum filtration and washed with methyl ferf-butyl ether (2 x 250 mL). The solid was collected and dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 18 hours to afford C101 on Celite. Yield: 57.6 g total = C101 + Celite; 16.61 g C101 , 28.1 mmol, 91%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.75-8.95 (br s, 2H), 8.65 (s, 1 H), 8.21 (s, 1 H), 7.30-7.58 (m, 10H), 6.83 (br s, 1 H), 6.65 (br s, 1 H), 6.17 (s, 1 H), 5.30 (s, 2H), 5.03 (s, 2H), 4.45 (br s, 1 H), 4.22 (br s, 2H), 3.77 (m, 1 H), 3.36 (m, 1 H), 3.22 (m, 1 H). 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ -76.0 (s, 3F). HPLC retention time 5.81 minutes; XBridge C8 column (4.6 x 75 mm, 3.5 μηη); column temperature 45 °C; flow rate 2.0 mL/minute; detection UV 210 nm, 230 nm, and 254 nm; mobile phase: solvent A = methanesulfonic acid (5%) in 10 mmol sodium octylsulfonate, solvent B = acetonitrile (100%); gradient elusion: 0-1.5 minutes solvent A (95%) and solvent B (5%), 1.5-8.5 minutes solvent A (5%) and solvent B (95%), 8.5-10.0 minutes solvent A (5%) and solvent B (95%), 10.01-12.0 minutes solvent A (95%) and solvent B (5%); total run time 12.0 minutes.

Step 9: Preparation of C90. A suspension of C101 (67.0 g, 30% activity on Celite = 33.9 mmol) in acetonitrile (281 .4 mL) was treated with molecular sieves 4AE (40.2 g), C5 (17.9 g, 33.9 mmol), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (10.4 g, 84.9 mmol) and the mixture was stirred at 40°C for 16 hours. The reaction mixture was cooled to 20 °C, filtered under vacuum and the filter cake washed with acetonitrile (2 x 100 mL). The filtrate was concentrated under vacuum to a volume of -50 mL. The solution was diluted with ethyl acetate (268.0 mL) and washed with 10% aqueous citric acid (3 x 134 mL) followed by 5% aqueous sodium chloride (67.0 mL). The organic layer was dried over magnesium sulfate and filtered under vacuum. The filter cake was washed with ethyl acetate (2 x 50 mL) and the filtrate was concentrated to a volume of -60 mL. The filtrate was added slowly to heptane (268 mL) with stirring and the slurry was stirred at 20 °C for 1 hour. The slurry was filtered under vacuum and the filter cake washed with a mixture of heptane and ethyl acetate (4: 1 , 2 x 27 mL). The solid was collected and dried under vacuum for 12 hours at 50 °C to afford a solid. The crude product was purified via chromatography on silica gel (ethyl acetate / 2-propanol), product bearing fractions were combined and the volume was reduced to -60 mL. The solution was added dropwise to heptane (268 mL) with stirring. The slurry was stirred at room temperature for 3 hours, filtered and washed with heptane and ethyl acetate (4: 1 , 2 x 27 mL). The solid was collected and dried under vacuum for 12 hours at 50 °C to afford C90 as a solid. Yield: 16.8 g, 18.9 mmol, 58%. LCMS m/z 889.4 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-cfe) 1 1.90 (br s, 1 H), 9.25 (d, J=8.7 Hz, 1 H), 8.40 (br s, 1 H), 7.98 (s, 1 H), 7.50-7.54 (m, 2H), 7.32- 7.47 (m, 8H), 7.28 (s, 1 H), 6.65 (br s, 1 H), 6.28 (br s, 1 H), 5.97 (s, 1 H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 5.18 (dd, J=8.8, 5 Hz, 1 H), 4.99 (s, 2H), 4.16-4.28 (m, 2H), 3.74-3.80 (m, 1 H), 3.29-3.41 (m, 1 H), 3.13-3.23 (m, 1 H), 1 .42 (s, 9H), 1 .41 (s, 3H), 1.39 (br s, 12H).

Step 10: Preparation of C91. A solution of C90 (14.5 g, 16.3 mmol) in anhydrous N,N- dimethylformamide (145.0 mL) was treated with sulfur trioxide /V,/V-dimethylformamide complex (25.0 g, 163.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 45 minutes, then transferred to a stirred mixture of 5% aqueous sodium chloride (290 mL) and ethyl acetate (435 mL) at 0 °C. The mixture was warmed to 18 °C and the layers separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (145 mL) and the combined organic layers washed with 5% aqueous sodium chloride (3 x 290 mL) followed by saturated aqueous sodium chloride (145 mL). The organic layer was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered through diatomaceous earth and the filter cake washed with ethyl acetate (72 mL). The filtrate was concentrated to a volume of 36 mL and treated with methyl ferf-butyl ether (290 mL), the resulting slurry was stirred at room temperature for 1 hour. The solid was collected by filtration, washed with methyl ferf- butyl ether (58 mL) and dried at 50 °C for 2 hours followed by 20 °C for 65 hours in a vacuum oven to yield C91 as a solid. Yield: 15.0 g, 15.4 mmol, 95%. LCMS m/z 967.6 (M-1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1 1.62 (br s, 1 H), 9.29 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1 H), 9.02 (s, 1 H), 7.58-7.61 (m, 2H), 7.38-7.53 (m, 9H), 7.27 (s, 1 H), 7.07 (s, 1 H), 6.40 (br d, J=8.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.55 (s, 2H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 5.20 (dd, J=8.8, 5.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.46 (br dd, half of ABX pattern, J=17.0, 5.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.38 (br dd, half of ABX pattern, J=17.0, 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.92- 3.98 (m, 1 H), 3.79-3.87 (m, 1 H), 3.07-3.17 (m, 1 H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.38 (s, 12H).

Step 11 : Preparation of C92. A solution of C91 (20.0 g, 20.6 mmol) in

dichloromethane (400 mL) was concentrated under reduced pressure (420 mmHg) at 45 °C to a volume of 200 mL. The solution was cooled to -5 °C and treated with 1 M boron trichloride in dichloromethane (206.0 mL, 206.0 mmol) added dropwise over 40 minutes. The reaction mixture was warmed to 15 °C over 1 hour with stirring. The slurry was cooled to -15 °C and treated with a mixture of 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (69.2 mL) and methyl ferf-butyl ether (400 mL), maintaining the temperature at -15 °C. The reaction mixture was warmed to 0 °C over 1 hour. The suspension was filtered using nitrogen pressure and the solid washed with methyl ferf-butyl ether (2 x 200 mL).

Nitrogen was passed over the solid for 2 hours. The solid was collected and suspended in methyl ferf-butyl ether (400 mL) for 1 hour with stirring at 18 °C. The suspension was filtered using nitrogen pressure and the solid washed with methyl ferf-butyl ether (2 x 200 mL). Nitrogen was passed over the resulting solid for 12 hours. A portion of the crude product was neutralized with 1 M aqueous ammonium formate to pH 5.5 with minimal addition of /V,/V-dimethylformamide to prevent foaming. The feed solution was filtered and purified via reverse phase chromatography (C-18 column; acetonitrile / water gradient with 0.2% formic acid modifier). The product bearing fractions were combined and concentrated to remove acetonitrile. The solution was captured on a GC-161 M column, washed with deionized water and blown dry with nitrogen pressure. The product was released using a mixture of methanol / water (10: 1 ) and the product bearing fractions were added to a solution of ethyl acetate (6 volumes). The solid was collected by filtration to afford C92 as a solid. Yield: 5.87 g, 9.28 mmol. LCMS m/z 633.3 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.22 (d, J=8.7 Hz, 1 H), 8.15 (s, 1 H), 7.26-7.42 (br s, 2H), 7.18-7.25 (m, 1 H), 6.99 (s, 1 H), 6.74 (s, 1 H), 6.32-6.37 (m, 1 H), 5.18 (dd, J=8.7, 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 4.33 (br d, J=4.6 Hz, 2H), 3.94-4.00 (m, 1 H), 3.60-3.68 (m, 1 H), 3.19-3.27 (m, 1 H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H).

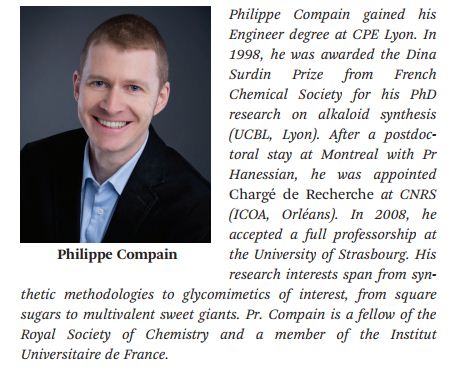

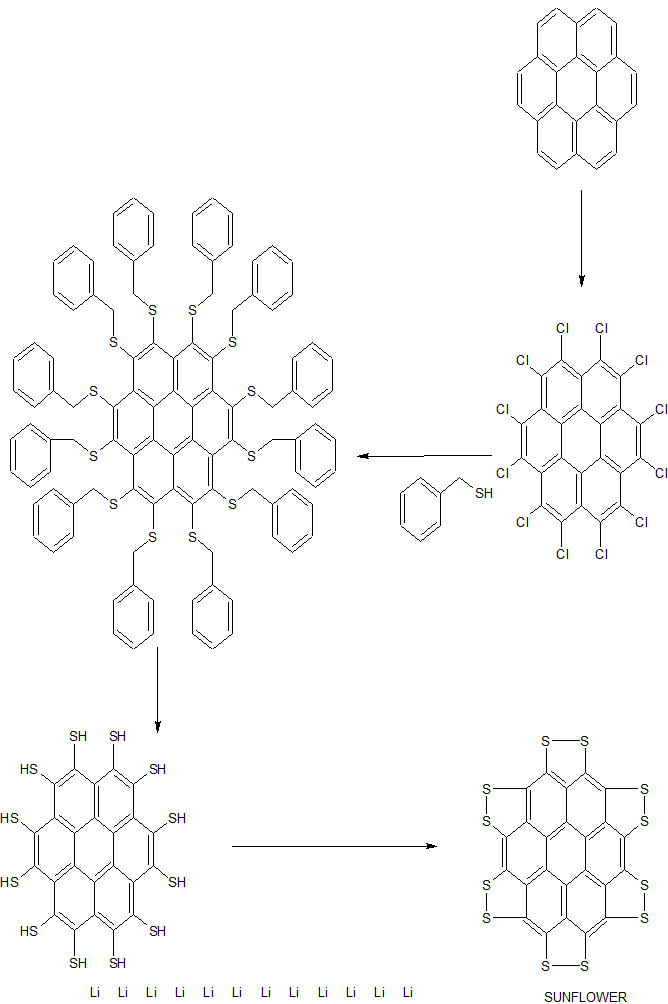

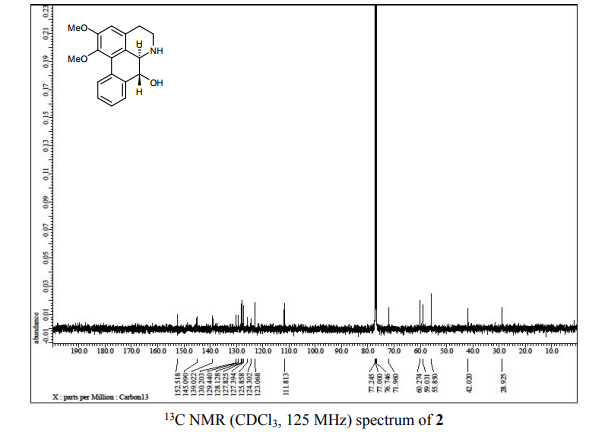

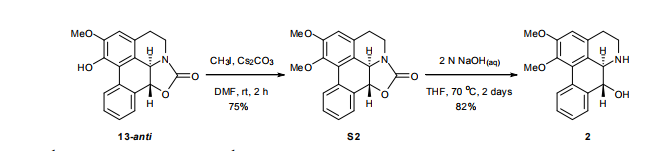

PAPER

Journal of Medicinal Chemistry (2014), 57(9), 3845-3855

Siderophore Receptor-Mediated Uptake of Lactivicin Analogues in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Jeremy Starr†, Matthew F. Brown†, Lisa Aschenbrenner§, Nicole Caspers¶, Ye Che⧧, Brian S. Gerstenberger†, Michael Huband§, John D. Knafels¶, M. Megan Lemmon§, Chao Li†, Sandra P. McCurdy§, Eric McElroy†, Mark R. Rauckhorst†, Andrew P. Tomaras§, Jennifer A. Young†, Richard P. Zaniewski§, Veerabahu Shanmugasundaram⧧, and Seungil Han*¶

†Medicinal Chemistry, ⧧Computational Chemistry, §Antibacterials Research Unit, and ¶Structural Biology, Pfizer Global Research and Development, Eastern Point Road, Groton, Connecticut 06340, United States

J. Med. Chem., 2014, 57 (9), pp 3845–3855

DOI: 10.1021/jm500219c

Publication Date (Web): April 2, 2014

Copyright © 2014 American Chemical Society

Abstract

Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens are an emerging threat to human health, and addressing this challenge will require development of new antibacterial agents. This can be achieved through an improved molecular understanding of drug–target interactions combined with enhanced delivery of these agents to the site of action. Herein we describe the first application of siderophore receptor-mediated drug uptake of lactivicin analogues as a strategy that enables the development of novel antibacterial agents against clinically relevant Gram-negative bacteria. We report the first crystal structures of several sideromimic conjugated compounds bound to penicillin binding proteins PBP3 and PBP1a from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and characterize the reactivity of lactivicin and β-lactam core structures. Results from drug sensitivity studies with β-lactamase enzymes are presented, as well as a structure-based hypothesis to reduce susceptibility to this enzyme class. Finally, mechanistic studies demonstrating that sideromimic modification alters the drug uptake process are discussed.

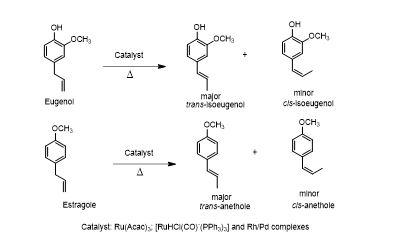

PAPER

Pyridone-Conjugated Monobactam Antibiotics with Gram-Negative Activity

Matthew F. Brown*†, Mark J. Mitton-Fry†, Joel T. Arcari†, Rose Barham†, Jeffrey Casavant†, Brian S. Gerstenberger†, Seungil Han⊥, Joel R. Hardink∥, Thomas M. Harris†, Thuy Hoang†, Michael D. Huband§, Manjinder S. Lall†, M. Megan Lemmon§, Chao Li†, Jian Lin∥, Sandra P. McCurdy§, Eric McElroy†, Craig McPherson§, Eric S. Marr⊥, John P. Mueller§, Lisa Mullins§, Antonia A. Nikitenko†, Mark C. Noe†, Joseph Penzien§, Mark S. Plummer†, Brandon P. Schuff†, Veerabahu Shanmugasundaram‡, Jeremy T. Starr†, Jianmin Sun†, Andrew Tomaras§, Jennifer A. Young†, and Richard P. Zaniewski§

†Worldwide Medicinal Chemistry, ‡Computational Chemistry, §Antibacterials Research Unit, ∥Pharmacokinetics, Dynamics & Metabolism, ⊥Structural Biology, Pfizer Global Research and Development, Eastern Point Road, Groton, Connecticut 06340, United States

J. Med. Chem., 2013, 56 (13), pp 5541–5552

DOI: 10.1021/jm400560z

Publication Date (Web): June 11, 2013

Copyright © 2013 American Chemical Society

Herein we describe the structure-aided design and synthesis of a series of pyridone-conjugated monobactam analogues with in vitro antibacterial activity against clinically relevant Gram-negative species including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli. Rat pharmacokinetic studies with compound 17 demonstrate low clearance and low plasma protein binding. In addition, evidence is provided for a number of analogues suggesting that the siderophore receptors PiuA and PirA play a role in drug uptake in P. aeruginosa strain PAO1.

![STR1]()

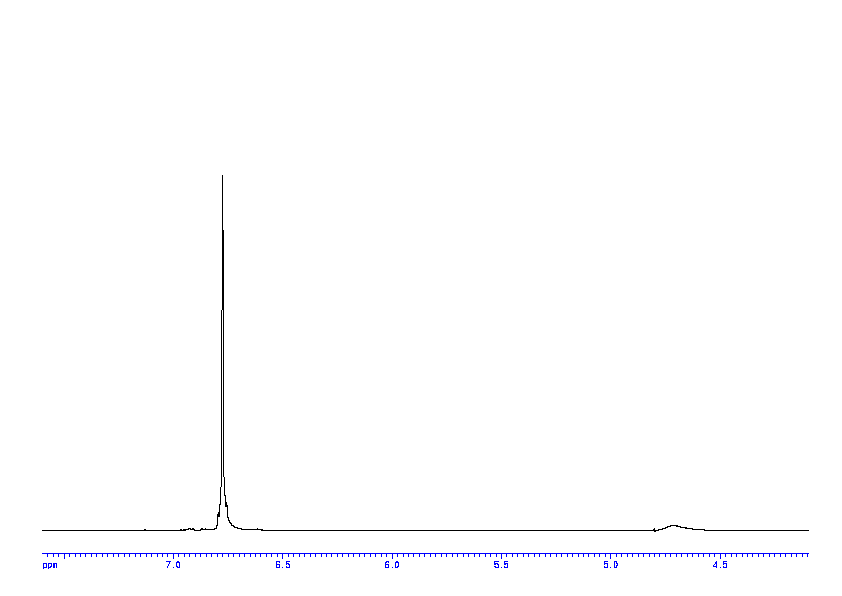

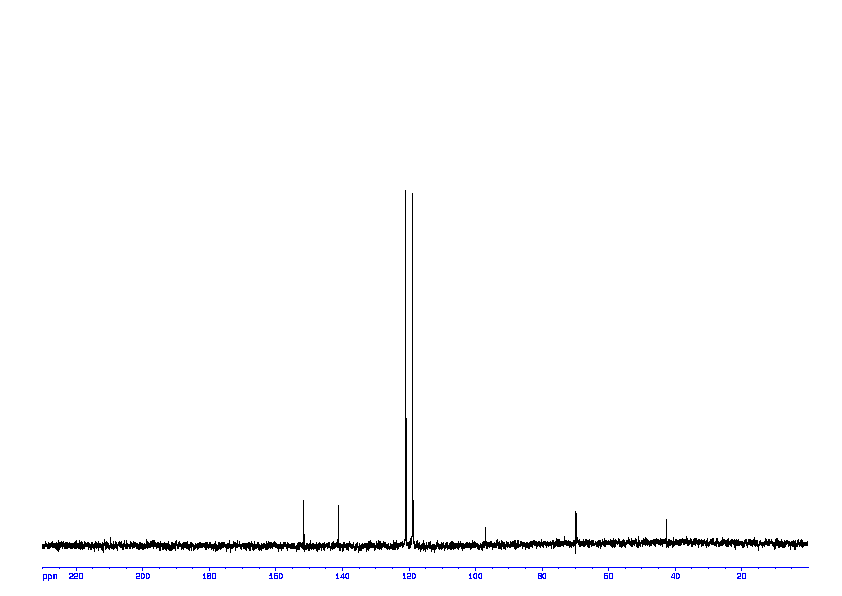

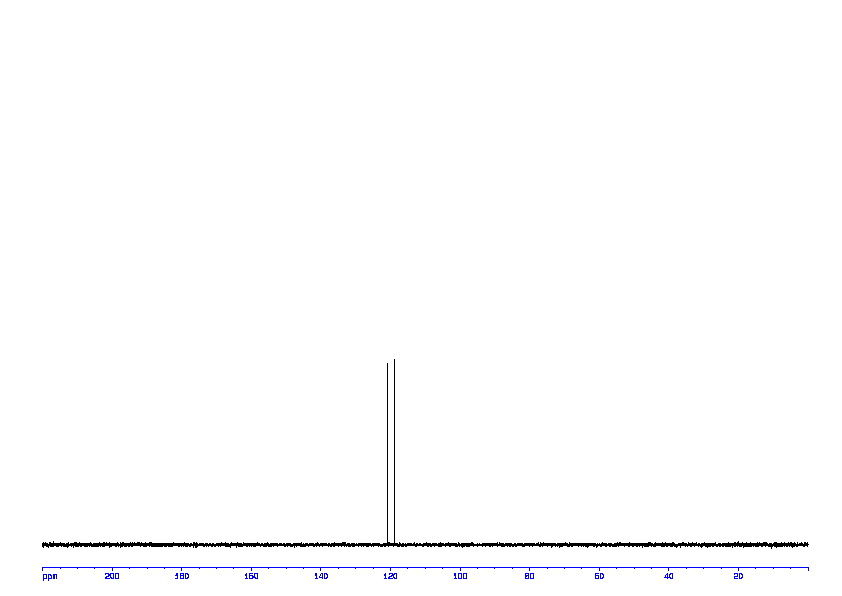

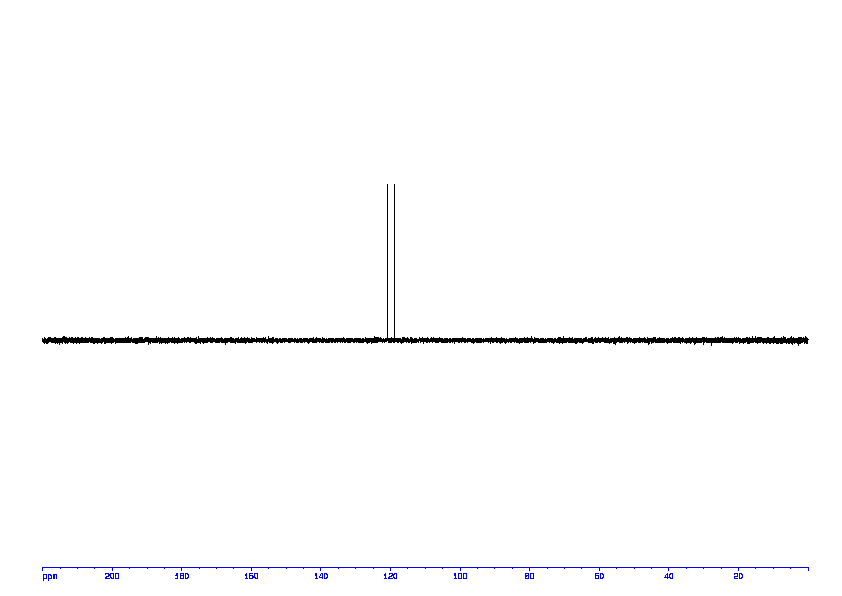

17 as a solid. Yield: 5.87 g, 9.28 mmol. LCMS m/z 633.3 (M+1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSOd6) δ 9.22 (d, J=8.7 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (s, 1H), 7.26-7.42 (br s, 2H), 7.18-7.25 (m, 1H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 6.74 (s, 1H), 6.32-6.37 (m, 1H), 5.18 (dd, J=8.7, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (br d, J=4.6 Hz, 2H), 3.94-4.00 (m, 1H), 3.60-3.68 (m, 1H), 3.19-3.27 (m, 1H), 1.40 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H).

Nc1nc(cs1)\C(=N\OC(C)(C)C(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@H]3C(=O)N([C@@H]3CNC(=O)NCC2=CC(=O)C(O)=CN2O)S(=O)(=O)O

PAPER

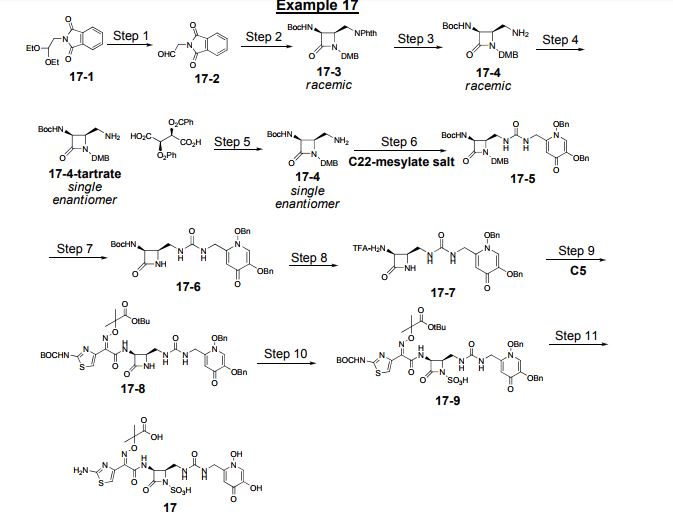

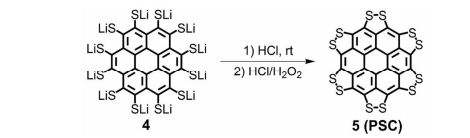

Process Development for the Synthesis of Monocyclic β-Lactam Core 17

Manjinder S. Lall* ![]() , Yong Tao*, Joel T. Arcari, David C. Boyles, Matthew F. Brown, David B. Damon, Susan C. Lilley, Mark J. Mitton-Fry, Jeremy Starr

, Yong Tao*, Joel T. Arcari, David C. Boyles, Matthew F. Brown, David B. Damon, Susan C. Lilley, Mark J. Mitton-Fry, Jeremy Starr ![]() , Andrew Morgan Stewart III, and Jianmin Sun

, Andrew Morgan Stewart III, and Jianmin Sun

Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development, Eastern Point Road, Groton, Connecticut 06340, United States

Org. Process Res. Dev., Article ASAP

DOI: 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00359

Publication Date (Web): January 4, 2018

Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society

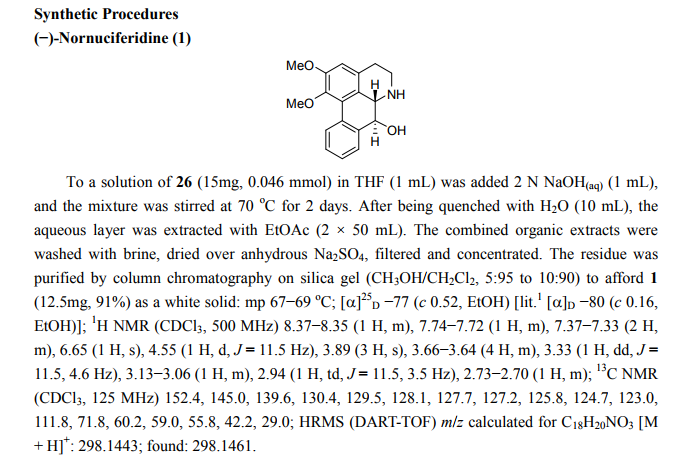

Process development and multikilogram synthesis of the monocyclic β-lactam core 17 for a novel pyridone-conjugated monobactam antibiotic is described. Starting with commercially available 2-(2,2-diethoxyethyl)isoindoline-1,3-dione, the five-step synthesis features several telescoped operations and direct isolations to provide significant improvement in throughput and reduced solvent usage over initial scale-up campaigns. A particular highlight in this effort includes the development of an efficient Staudinger ketene–imine [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of N-Boc-glycine ketene 12 and imine 9 to form racemic β-lactam 13 in good isolated yield (66%) and purity (97%). Another key feature in the synthesis involves a classical resolution of racemic amine 15 to afford single enantiomer salt 17 in excellent isolated yield (45%) with high enantiomeric excess (98%).

![Figure]()

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/suppl/10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00359/suppl_file/op7b00359_si_001.pdf

Nc1nc(cs1)\C(=N\OC(C)(C)C(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@H]3C(=O)N([C@@H]3CNC(=O)NCC2=CC(=O)C(O)=CN2O)S(=O)(=O)O

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

J. Med. Chem., 2013, 56 (13), pp 5541–5552

DOI: 10.1021/jm400560z

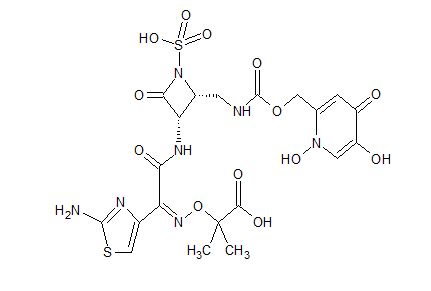

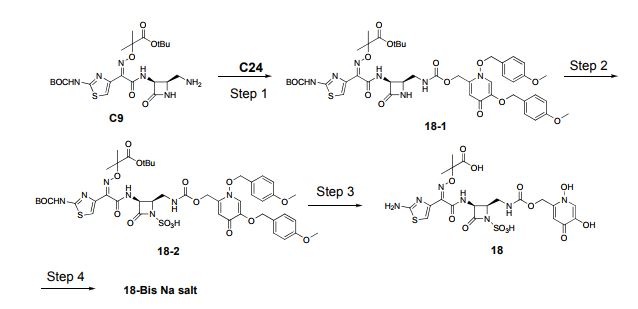

OXYGEN ANALOGUE…………..

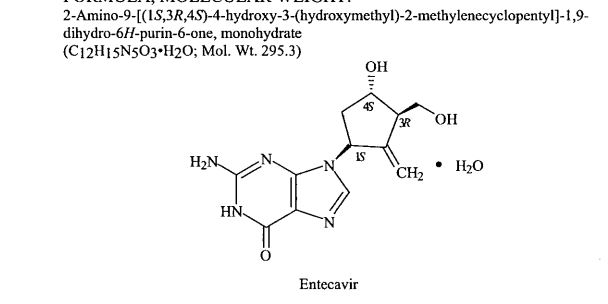

1380110-45-1, C20 H23 N7 O13 S2, 633.57

Propanoic acid, 2-[[(Z)-[1-(2-amino-4-thiazolyl)-2-[[(2R,3S)-2-[[[[(1,4-dihydro-1,5-dihydroxy-4-oxo-2-pyridinyl)methoxy]carbonyl]amino]methyl]-4-oxo-1-sulfo-3-azetidinyl]amino]-2-oxoethylidene]amino]oxy]-2-methyl-

![STR2]()

18 as a light yellow solid. Yield: 43 mg, 0.068 mmol, 51%. LCMS m/z 634.4 (M+1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), characteristic peaks: δ 9.29 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.04-7.10 (m, 1H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.75 (s, 1H), 5.05-5.30 (m, 3H), 4.00-4.07 (m, 1H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.41 (s, 3H).

Nc1nc(cs1)\C(=N\OC(C)(C)C(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@H]3C(=O)N([C@@H]3CNC(=O)OCC2=CC(=O)C(O)=CN2O)S(=O)(=O)O

Step 4: Preparation of 18-Bis Na salt. A suspension of 5 (212 mg, 0.33 mmol) in water (10 mL) was cooled to 0 oC and treated with a solution of sodium bicarbonate (56.4 mg, 0.67 mmol) in water (2 mL), added dropwise. The reaction mixture was cooled to -70 oC (frozen) and lyophilized to afford 18-Bis Na salt as a white solid. Yield: 210 mg, 0.31 mmol, 93%. LCMS m/z 632.5 (M-1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 7.87 (s, 1H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.92 (s, 1H), 5.35 (d, J=5 Hz, 1H), 5.16 (s, 2H), 4.46-4.52 (m, 1H), 3.71 (dd, half of ABX pattern, J=14.5, 6 Hz, 1H), 3.55 (dd, half of ABX pattern, J=14.5, 6 Hz, 1H), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1.42 (s, 3H).

WO 2012073138

Example 5

disodium 2-({[(1Z)-1 -(2-amino-1 ,3-thiazol-4-yl)-2-({(2R,3S)-2-[({[(1 ,5-dihydroxy-4- oxo-1 ,4-dihydropyridin-2-yl)methoxy]carbonyl}amino)methyl]-4-oxo-1 – sulfonatoazetidin-3-yl}amino)-2-oxoethylidene]amino}oxy)-2-methylpropanoate

(C104-Bis Na salt).

Step 1 : Preparation of C102. A solution of C28 (300 mg, 0.755 mmol) in

tetrahydrofuran (10 mL) was treated with 1 , 1 ‘-carbonyldiimidazole (379 mg, 2.26 mmol) at room temperature and stirred for 20 hours. The yellow reaction mixture was treated with a solution of C9 (286 mg, 0.543 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (25 mL). The mixture was stirred for 6 hours at room temperature, then treated with water (20 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 x 25 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was purified via chromatography on silica gel (heptane / ethyl acetate / 2-propanol) to afford C102 as a light yellow solid. Yield: 362 mg, 0.381 mmol, 62%. LCMS m/z 950.4 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-de), characteristic peaks: δ 9.31 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1 H), 8.38 (s, 1 H), 8.00 (s, 1 H), 7.41 (br d, J=8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (br d, J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (s, 1 H), 6.10 (s, 1 H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 4.92 (br s, 4H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 1.45 (s, 9H), 1.38 (s, 9H). Step 2: Preparation of C103. A solution of C102 (181 mg, 0.191 mmol) in anhydrous /V,/V-dimethylformamide (2.0 mL) was treated with sulfur trioxide pyridine complex (302 mg, 1.91 mmol). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 6 hours, then cooled to 0 °C and quenched with water. The resulting solid was collected by filtration and dried in vacuo to yield C103 as a white solid. Yield: 145 mg, 0.14 mmol, 74%. APCI m/z 1028.5 (M-1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), characteristic peaks: δ 1 1.65 (br s, 1 H), 9.37 (d, J=8.6 Hz, 1 H), 8.87 (s, 1 H), 7.49 (br d, J=8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (br d, J=8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (s, 1 H), 7.01 (br d, J=8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (br d, J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.43 (s, 2H), 5.20 (dd, J=8.4, 6 Hz, 1 H), 4.01-4.07 (m, 1 H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.50- 3.58 (m, 1 H), 3.29-3.37 (m, 1 H), 1.44 (s, 9H), 1.37 (s, 9H). Step 3: Preparation of C104. A solution of C103 (136 mg, 0.132 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (5 mL) was treated with 1 M boron trichloride in p-xylenes (0.92 mL, 0.92 mmol) and allowed to stir at room temperature for 40 minutes. The reaction mixture was cooled in an ice bath, quenched with water (0.4 mL), and transferred into a solution of methyl ferf-butyl ether: heptane (1 :2, 12 mL). The solvent was removed in vacuo and the crude product was purified via reverse phase chromatography (C-18 column; acetonitrile / water gradient with 0.1 % formic acid modifier) to yield C104 as a light yellow solid. Yield: 43 mg, 0.068 mmol, 51 %. LCMS m/z 634.4 (M+1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-de), characteristic peaks: δ 9.29 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.10 (s, 1 H), 7.04- 7.10 (m, 1 H), 7.00 (s, 1 H), 6.75 (s, 1 H), 5.05-5.30 (m, 3H), 4.00-4.07 (m, 1 H), 1 .42 (s, 3H), 1 .41 (s, 3H).

Step 4: Preparation of C104-Bis Na salt. A suspension of C104 (212 mg, 0.33 mmol) in water (10 mL) was cooled to 0 °C and treated with a solution of sodium bicarbonate (56.4 mg, 0.67 mmol) in water (2 mL), added dropwise. The reaction mixture was cooled to -70 °C (frozen) and lyophilized to afford C104-Bis Na salt as a white solid. Yield: 210 mg, 0.31 mmol, 93%. LCMS m/z 632.5 (M-1 ). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D20) δ 7.87 (s, 1 H), 6.94 (s, 1 H), 6.92 (s, 1 H), 5.35 (d, J=5 Hz, 1 H), 5.16 (s, 2H), 4.46-4.52 (m, 1 H), 3.71 (dd, half of ABX pattern, J=14.5, 6 Hz, 1 H), 3.55 (dd, half of ABX pattern, J=14.5, 6 Hz, 1 H), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1 .42 (s, 3H).

////////////Pfizer, monobactam, PF-?, preclinical, pf, pfizer

![Share]()

amcrasto@gmail.com

amcrasto@gmail.com

Open Access

Open Access

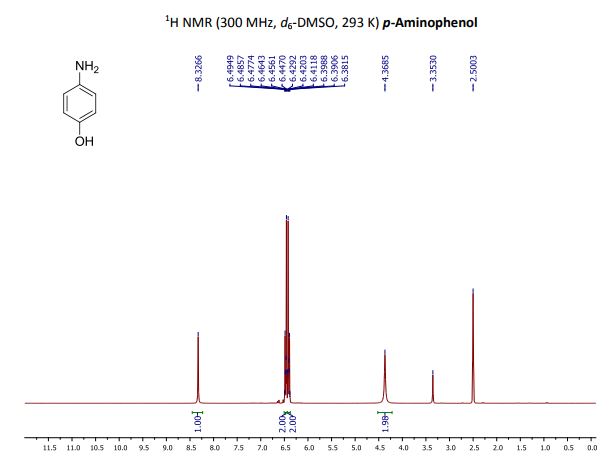

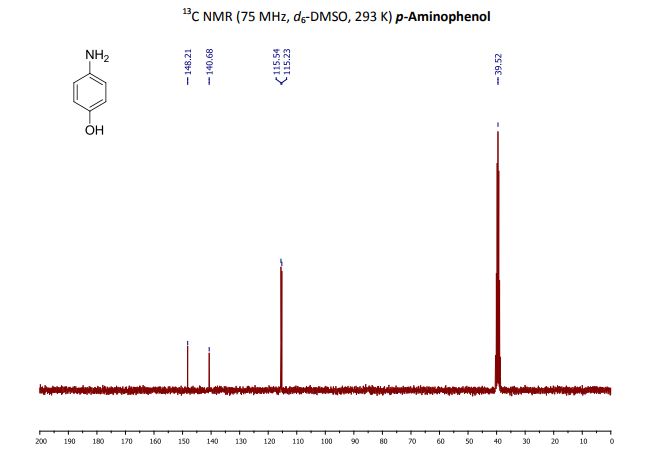

![2D [1H,1H]-TOCSY, 7.4 spectrum for 4-Aminophenol](http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/ftp/pub/bmrb/metabolomics/entry_directories/bmse000462/nmr/set01/spectra/HH_TOCSY.png)

![2D [1H,13C]-HSQC, 7.4 spectrum for 4-Aminophenol](http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/ftp/pub/bmrb/metabolomics/entry_directories/bmse000462/nmr/set01/spectra/1H_13C_HSQC.png)

![2D [1H,13C]-HMBC, 7.4 spectrum for 4-Aminophenol](http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/ftp/pub/bmrb/metabolomics/entry_directories/bmse000462/nmr/set01/spectra/1H_13C_HMBC.png)